A few years ago, I went to India for a meditation retreat at the Osho International Meditation Centre. My accommodation happened to be in a building named Rinzai, after the great Zen master Rinzai Gigen, founder of the Rinzai school of Zen. At the time, I knew little about him. During the retreat, one of the core practices was the Osho Evening Meeting—a mix of dance, celebration, and silent meditation. Between these moments of joyful movement and stillness, discourses by Osho were streamed on large screens.

By chance, the talks during my stay were about Zen Master Hyakujo. I was immediately captivated by the paradoxical and surprising nature of these Zen stories. Something in them stirred me, and I found myself drawn to the world of Zen. That was my first meaningful contact with Zen teachings—and indirectly, with the tradition that Rinzai Gigen founded.

Months later, still exploring Zen and curious about who Rinzai Gigen actually was, I came across a book by an English Zen master named Daizan Roshi. His writing struck me immediately—it was direct, practical, and refreshingly free of spiritual fluff. There was a “just-do-it” spirit that deeply resonated with me. I was also drawn by the fact that Daizan Roshi lived in London, not far from me, and was leading a thriving community in the Rinzai tradition called Zenways. Something about it felt like coming home. I sensed a kind of intuitive trust, especially after meeting a few of the people involved. Before long, I joined Zenways and became a formal student of Rinzai Zen.

It’s worth noting that there are two main schools of Zen: Sōtō and Rinzai, plus a smaller one called Ōbaku-shū. All of them aim to free us from the entanglement of our own minds—to help us see through delusion and awaken to reality as it is. It’s a monumental task that, at times, can feel almost impossibly difficult. Learning to see clearly—beyond the conditioned filters of our thinking mind—is no small feat. I imagine that Rinzai Gigen himself struggled with this before his own awakening, and only then was able to guide others toward theirs.

What amazes me is that more than 1,000 years later, his teachings have somehow reached me.

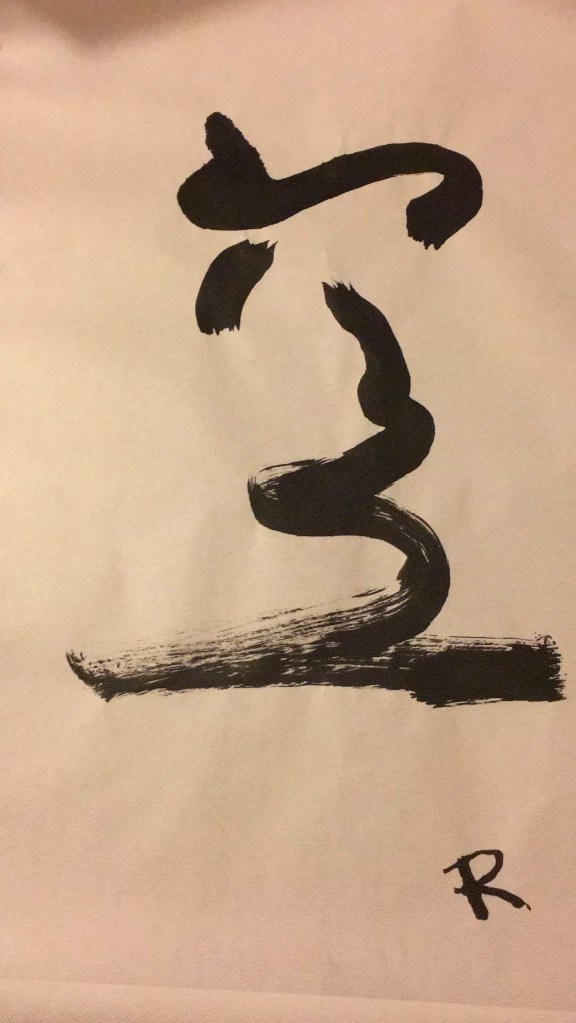

The figure depicted in the photo above is Linji Yixuan—known in Japan as Rinzai Gigen. He lived in 9th-century China, and founded what would become the Rinzai school of Zen. That his teachings have survived for over a millennium and continue to inspire people today feels almost miraculous. How many people did he influence? How many generations carried his message forward? And what is the essence of what he passed down?

I suspect each person touched by Rinzai’s teachings would give a different answer. Here’s mine: Zen practice, as I’ve come to understand it, is about creating the conditions in which the mind can fully meet reality. So often, our thoughts pull us away—into fantasies, fears, judgments, preferences. A split is created between what’s happening and where our attention goes. Zen practice helps us close that gap. It trains us to return the mind to the present moment, to the activity at hand. In the Rinzai tradition, there are many ways to do this—many “Zen ways,” as the name of my community suggests.

Here are some of the practices I’ve engaged in since becoming a student:

- Zazen (sitting meditation), which remains the heart of my practice.

- Kinhin, or walking meditation.

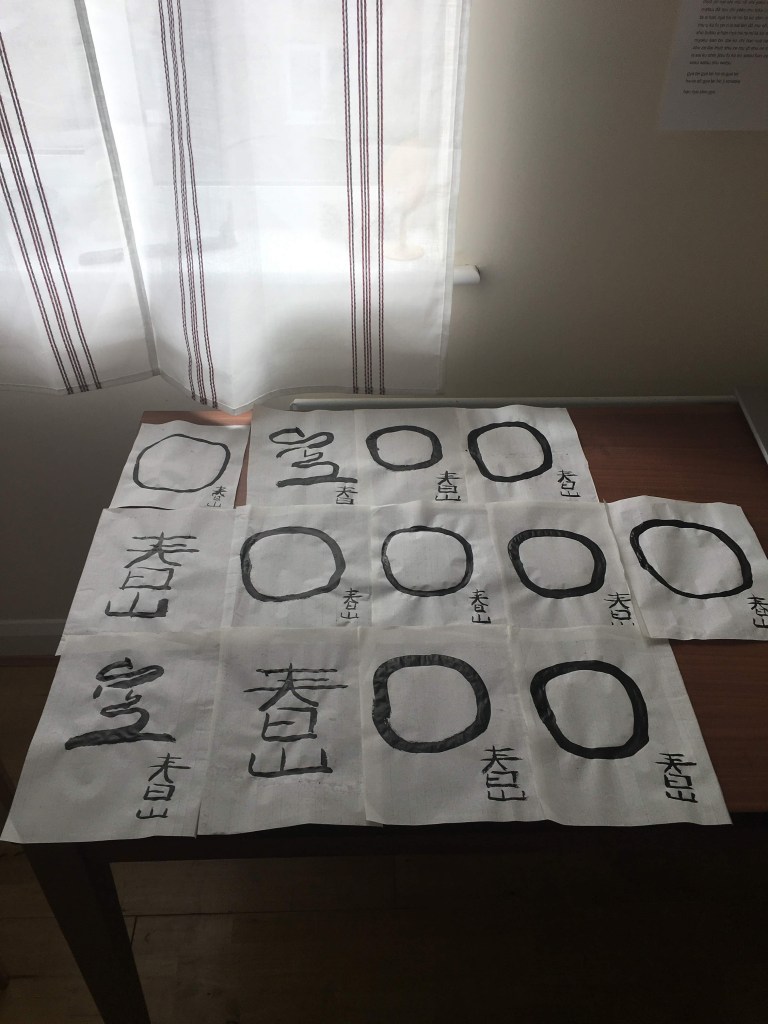

- Zen calligraphy, Zen running, and Samu, which is working meditation.

- Koan practice, which helps shake the mind out of its conceptual habits.

- Sanzen, a private meeting with a teacher.

- Haiku, the art of brief, evocative poetry.

- Chanting, serving meals, all-night meditation, and Dyad practice (paired inquiry).

- Mountain walking retreats.

- And a variety of energetic awareness exercises known as Naikan, which were developed much later by Hakuin Ekaku, one of the great revivers of Rinzai Zen.

I’ve likely forgotten a few, but I intend to write more about these practices in future reflections. What fascinates me is the sheer variety of methods—each a different doorway into the same house. Each one has shown me, again and again, where my resistance lies, how my mind creates unnecessary suffering, and how I can come back to what’s real.

Whether Rinzai Gigen himself originated all these practices is doubtful—many evolved later. But I feel a powerful connection with him. Maybe because I first encountered his name in India. Maybe because now, I seem to see him everywhere—guiding, pointing, laughing even. There’s something timeless in his presence, and in the lineage that bears his name. And perhaps that’s the greatest teaching of all: that we’re never really far from the truth—we’ve just forgotten how to look.

I am not totally sure whether Rinzai Gigen himself started all these practices in his school. Most likely, they have been developed by other Zen Masters along the way. For example, I know that the Naikan practices have been introduced by Hakuin Ekaku who lived much later compared to Rinzai Gigen. However, I somehow feel a strong connection with Rinzai Gigen as I first ‘met’ him in India and I now see him everywhere.